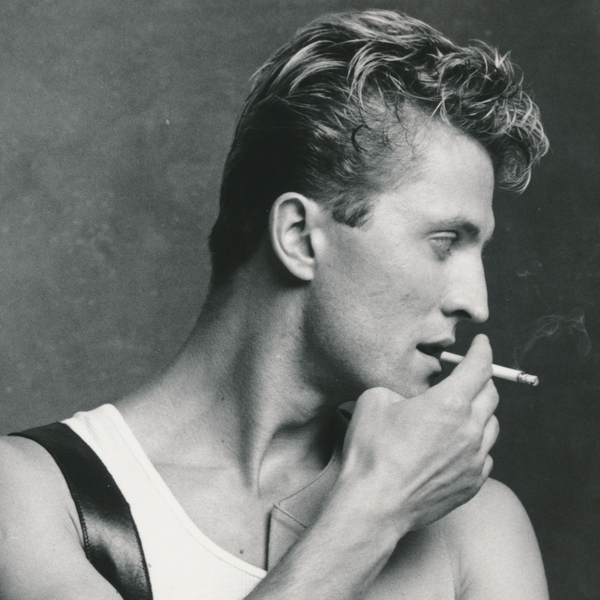

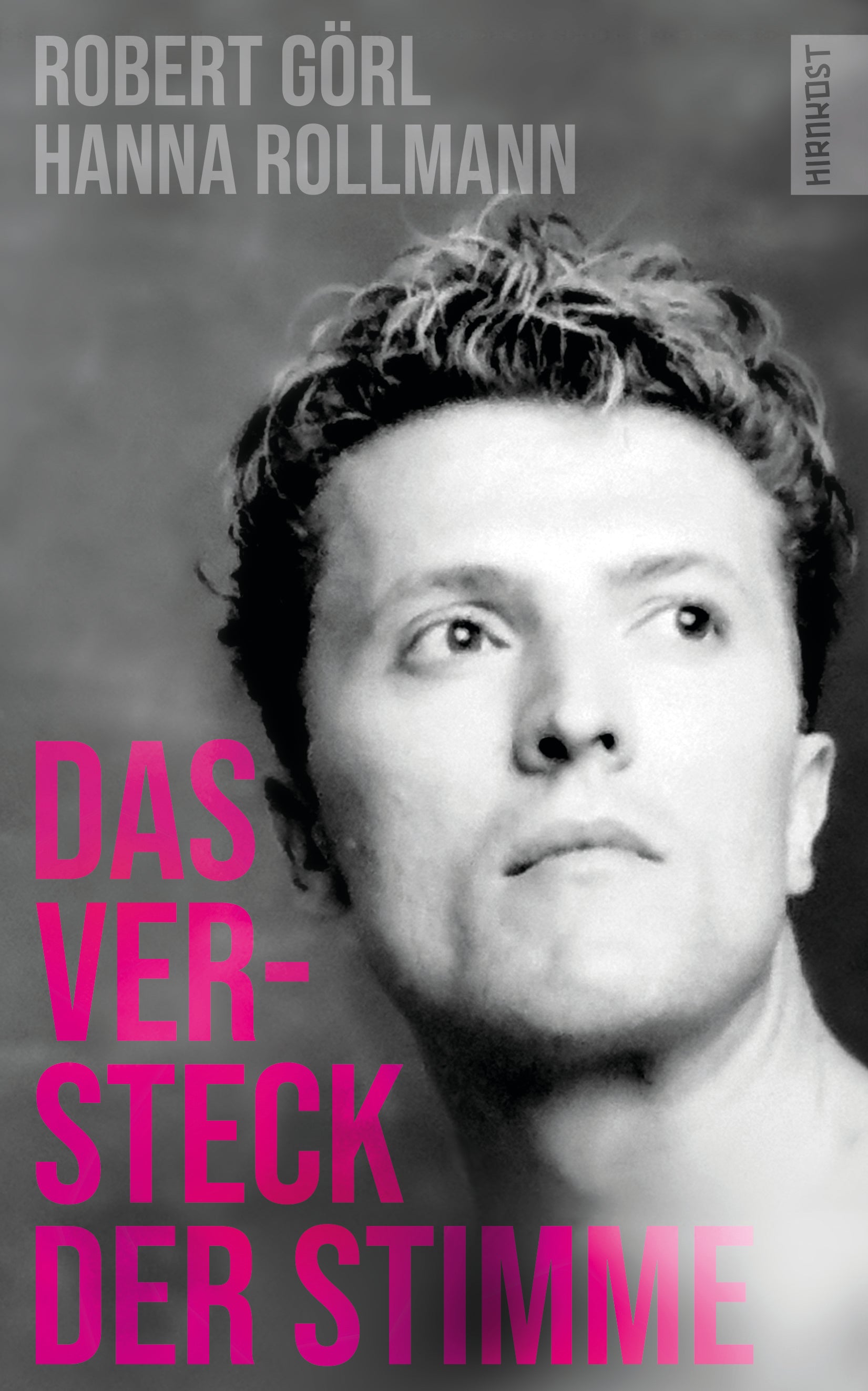

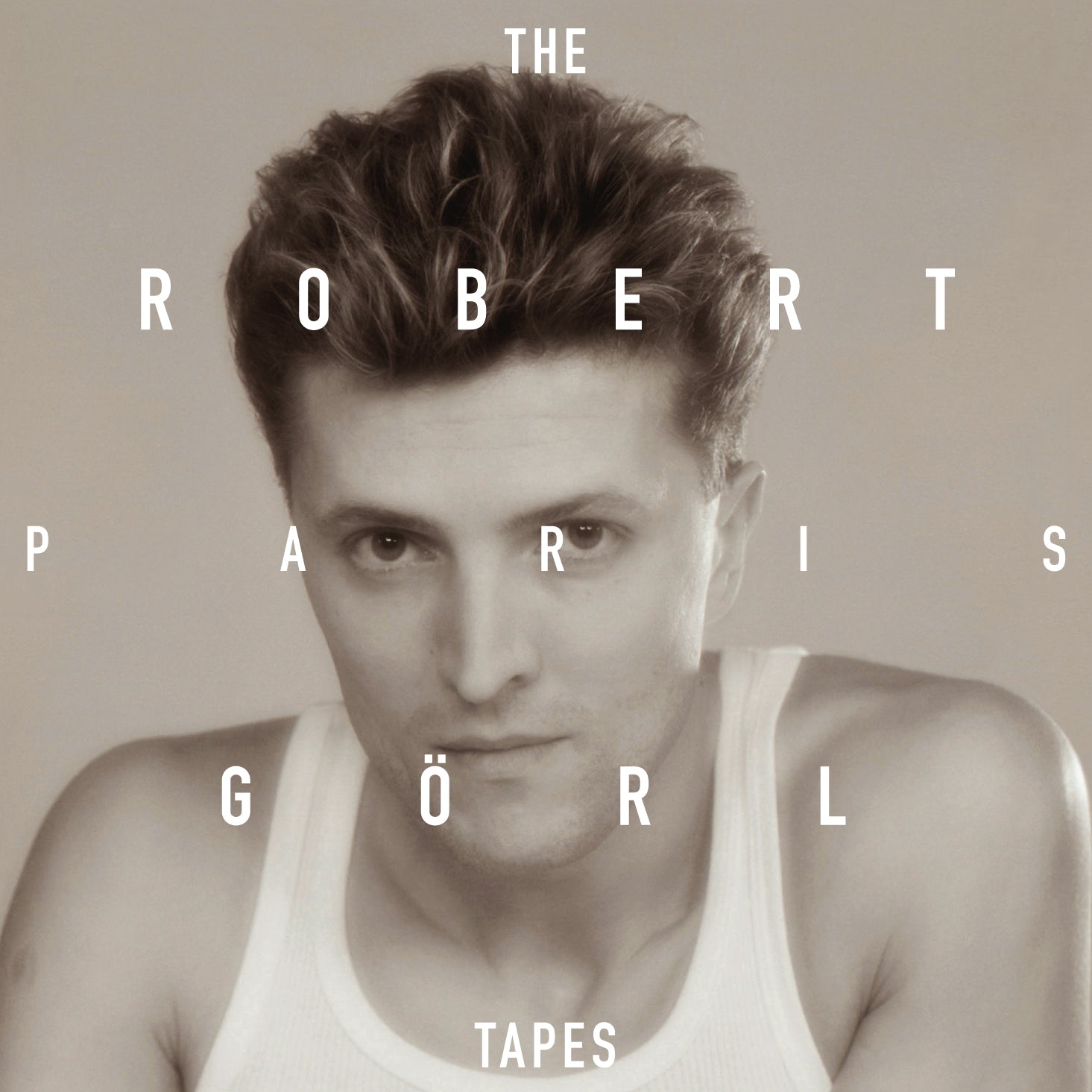

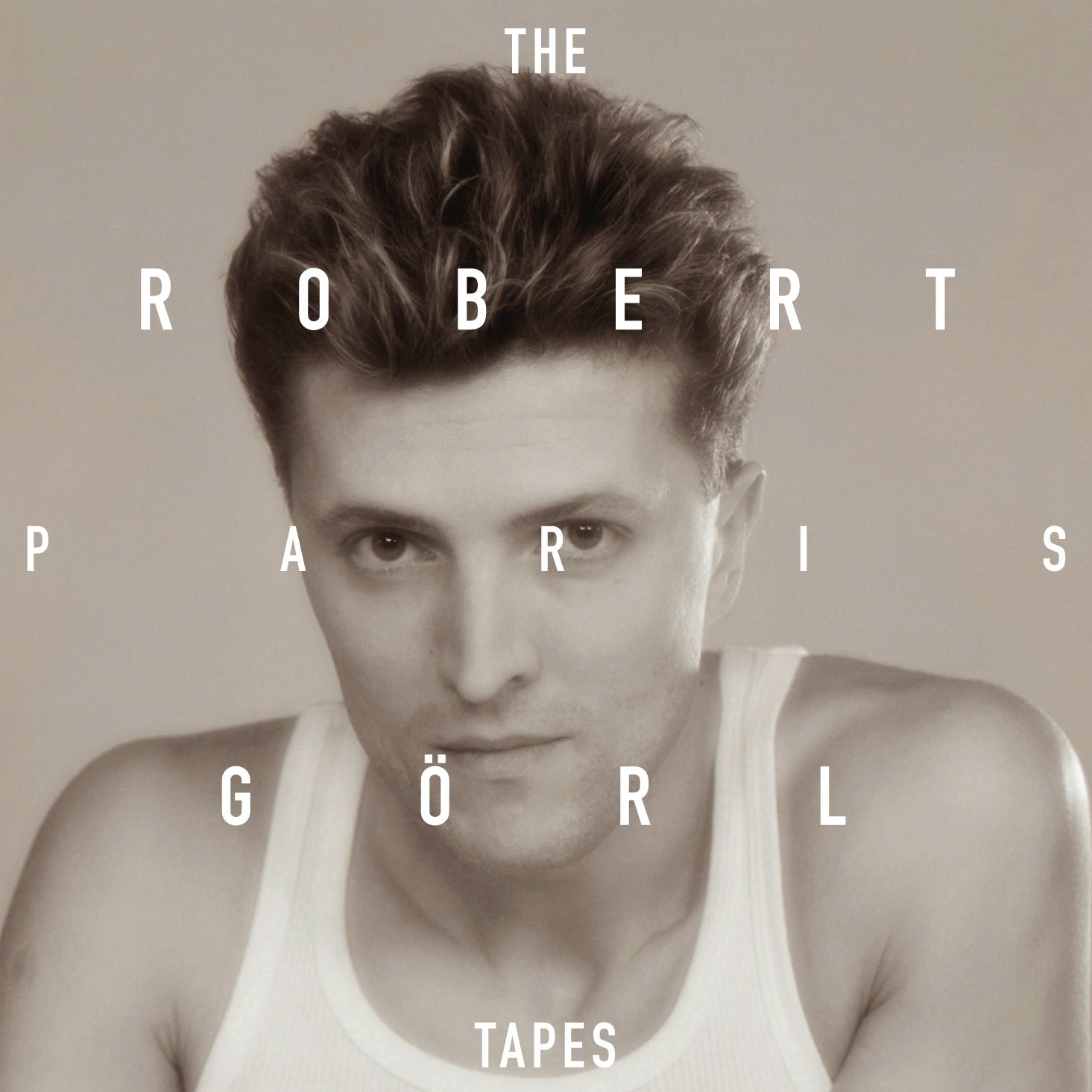

Robert Görl

Robert Görl, von der legendären DAF, schuf während einer persönlichen Krise in Paris, ergreifende elektronische Skizzen. Allein mit einem Ensoniq ESQ-1 schuf er emotionale Klänge, die die Zukunft der elektronischen Musik erahnen ließen. Diese aus Verzweiflung geborenen Skizzen beleuchten ein kreatives Wiederaufleben inmitten der Tiefen des Lebens.

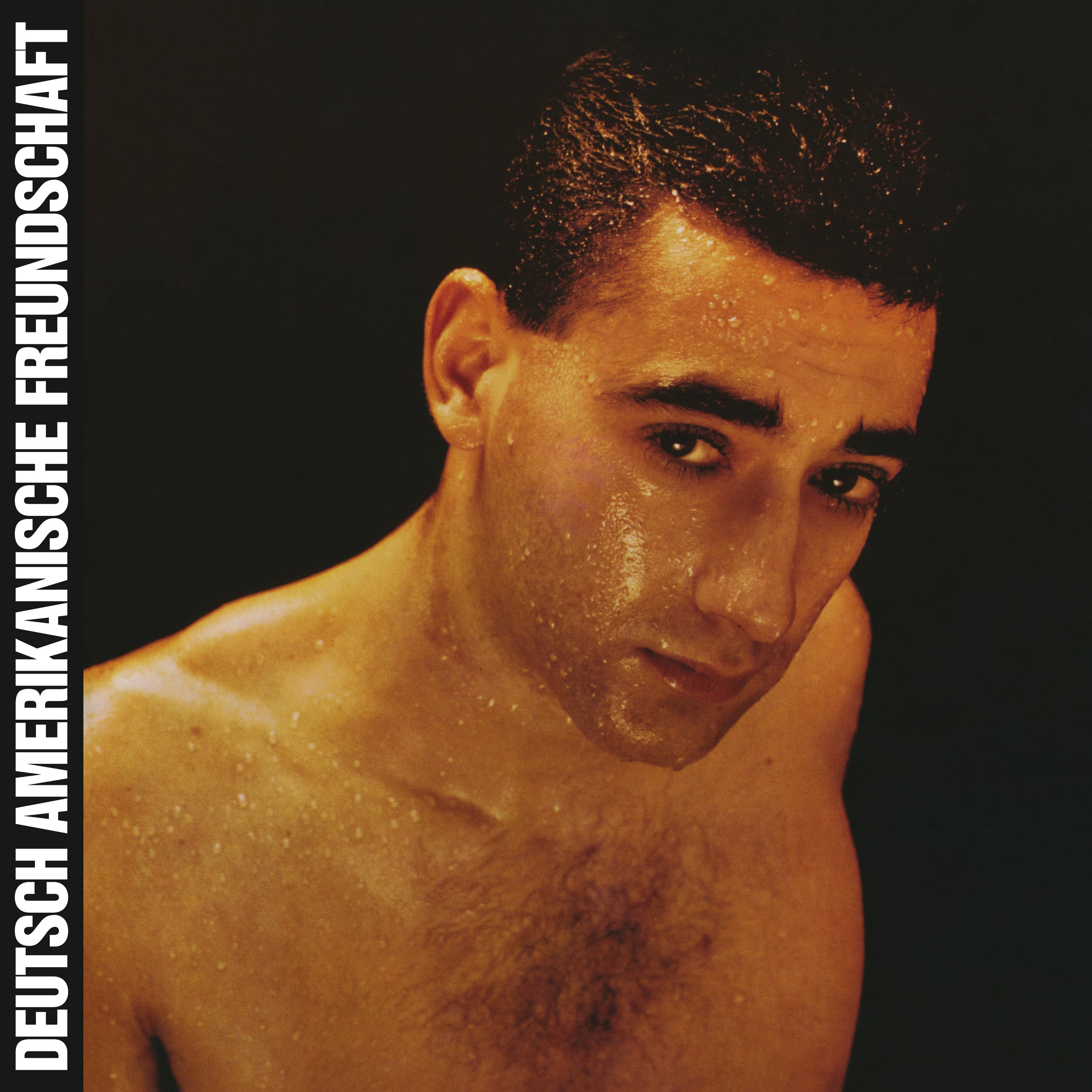

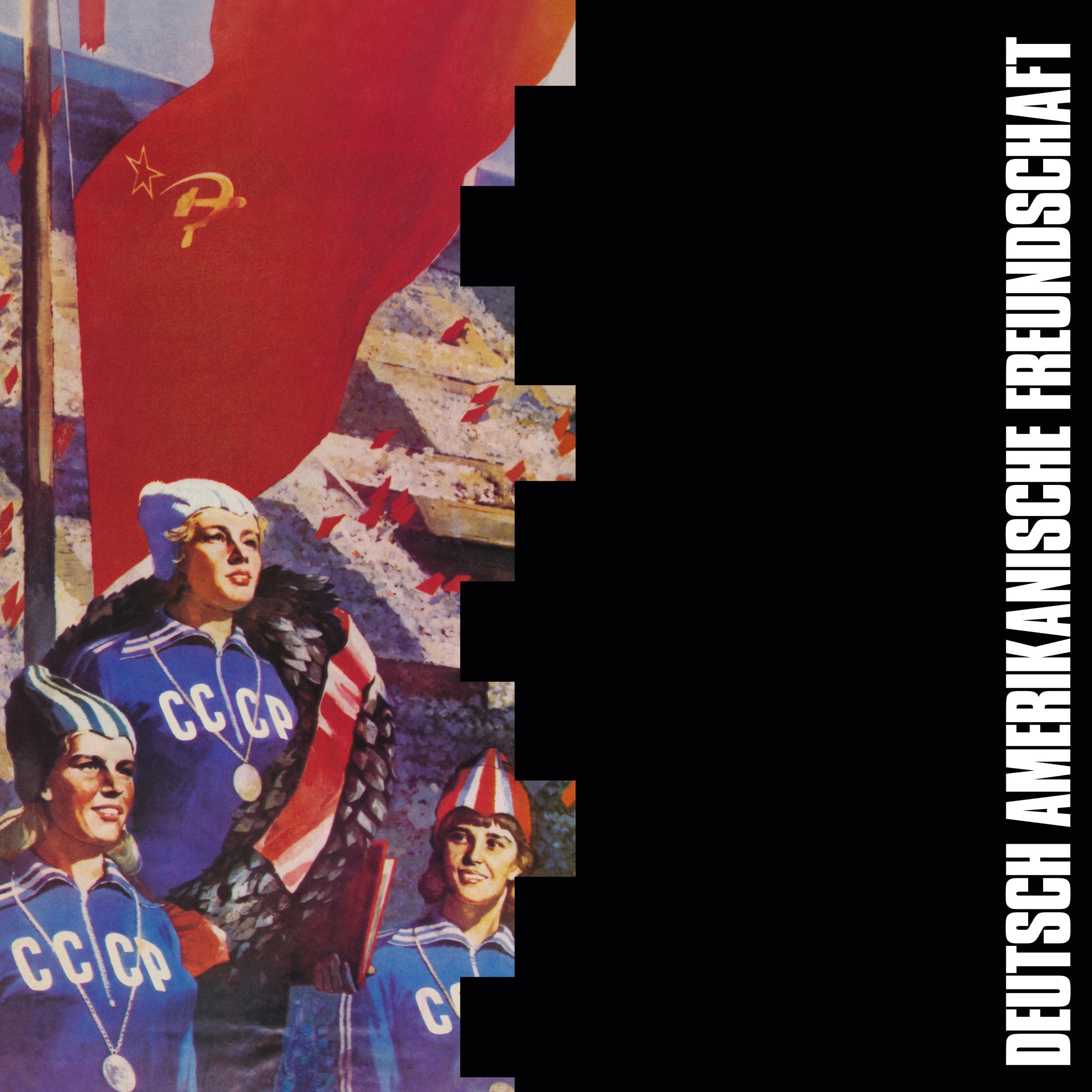

Alles beginnt mit einem Ende, das jedoch nicht für immer endet. Anfang der 1980er Jahre feierten Robert Görl und Gabi Delgado als Duo Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft großen Erfolg, bis sie sich 1982 nach einem Streit trennten. 1986, nach einem kurzlebigen Versuch einer Reunion, kam es erneut zur Trennung, diesmal für deutlich längere Zeit. Robert Görl sagt, diese Zeit sei für ihn sehr schwierig gewesen und er sei von seinem musikalischen Partner und Freund tief enttäuscht gewesen; bei der Arbeit an der LP 1st Step to Heaven kamen sie so sehr in die Quere, dass er jegliche Lust am Musizieren verlor.

Und so beschloss er, etwas Neues auszuprobieren und ging nach New York, um am renommierten Stella Adler Studio of Acting Schauspiel zu studieren. Er probte ein Semester lang Shakespeare und andere Klassiker und hätte vielleicht eine Bühnenkarriere starten können; doch nach der Rückkehr von einem kurzen Heimtrip wurde er bei seiner Ankunft in New York festgenommen und verhört. Der Einwanderungsbeamte fragte ihn, was er in der Stadt mache, er antwortete, er studiere Schauspiel – „Das ist interessant“, sagte der Beamte. Vier Tage später erhielt Görl per Post einen Bescheid, dass er gegen Einwanderungsgesetze verstoßen habe, da er in den USA nur mit einem Touristenvisum ein Studium absolviere; er müsse das Land daher sofort verlassen und dürfe die Vereinigten Staaten für die nächsten zehn Jahre nicht betreten.

Er hatte nun nicht nur keine Band mehr, er konnte auch nicht mehr studieren und nicht mehr in der Stadt bleiben, die er gerade lieben gelernt hatte. Das war jedoch nur der Anfang seiner Probleme. Als er zurück nach Deutschland flog, wurde er am Flughafen festgehalten. Man teilte ihm mit, die Bundeswehr suche schon seit geraumer Zeit nach ihm, da er sich vor seiner Wehrpflicht gedrückt habe; er dürfe das Land nicht verlassen und müsse sich innerhalb weniger Tage bei der Armee melden, sonst würde ihn die Feldjägerei festnehmen. Görl überlegte ein paar Tage, packte seine wenigen Habseligkeiten in einen Koffer, klemmte seinen frisch gekauften Synthesizer unter den Arm und setzte sich in einen Nachtzug von München nach Paris; schlaflos und mit rasendem Herzen wartete er auf die Grenzkontrolle, die ihm jedoch nicht einmal die Abteiltür öffnete. Am nächsten Morgen stand er am Gare de l’Est und machte sich auf die Suche nach einer billigen Unterkunft. Er wurde schließlich in Levallois-Perret, einem Vorort im Nordwesten von Paris, gefunden. Sein Plan war, etwa ein Jahr dort zu bleiben, bis er das Alter erreicht hatte, in dem er nicht mehr eingezogen werden konnte. Er hatte ein kleines Zimmer mit einer Küchenzeile und einem Waschbecken. Er kannte niemanden in der Stadt und wollte niemanden treffen; selbst wenn er gewollt hätte, wäre es schwierig gewesen, da er kein Französisch sprach.

Robert Görl saß nun allein in einer Pension in einem Pariser Vorort fest und verbrachte seine Tage – und vor allem seine Nächte – damit, Musik zu machen. Er benutzte seinen neuen, frisch erschienenen Synthesizer – einen ESQ-1 der Firma Ensoniq – er hatte acht Stimmen, einen eingebauten Sequenzer und Tausende vorprogrammierte Klänge. Es war eine Maschine, die fast wie die Workstations zu verwenden war, die die Produktion elektronischer Musik Ende der 1980er Jahre vereinfachen und dramatisch verändern sollten. In der Einsamkeit seines hermetischen Daseins gelang es Robert Görl, in die Zukunft der Musik vorzudringen: Nacht für Nacht tauchte er immer tiefer in die Möglichkeiten ein, die ihm der Synthesizer bot; er komponierte und legte musikalische Schichten übereinander; er formte Klänge, überarbeitete sie und löschte sie manchmal wieder; er arrangierte Rhythmen und Bässe und modulierte die Musik – insbesondere die tiefen Töne – so stark, dass sie zischender und „schmutziger“ klangen. Dadurch wurden die Lieder immer dramatischer und persönlicher. Sie spiegelten die Lebenskrise wider, in der sich Görl befand, waren ihm aber zugleich ein rechtzeitiges Heilmittel, um ihn von dem Gefühl zu befreien, in einer gescheiterten Existenz gefangen zu sein.

Ein halbes Jahr blieb er in der Pension in Levallois-Perret, bevor er bei zwei Freundinnen seiner Schwester unterkam. Doch nach einem Dreivierteljahr in Paris beschlich ihn das Gefühl, dringend nach Hause zurückkehren zu müssen. Und er hatte Glück: Als er nach München zurückkehrte, ließ ihn die Bundeswehr in Ruhe. Es ging bergauf. Die Zeit in Paris hatte ihm neuen Optimismus gegeben und auch seine Lust am Musizieren neu entfacht; er beschloss, aus den Liedern, die er auf seiner ESQ-1 komponiert und auf handelsübliche Kassetten aufgenommen hatte, nun ein Pop-Album zu machen. Er flog nach London, um Daniel Miller zu treffen, der die ersten Alben von DAF auf seinem Label Mute Records veröffentlicht hatte. Miller brachte ihn in Kontakt mit Dee Long, einem Progressive-Rock-Musiker, der damals in einer New-Wave-Band spielte. In Longs Studio in Südengland arrangierten Görl und Long neue Arrangements von Görls Paris-Stücken. Anschließend wollten sie die Musik in den Air Studios des Beatles-Produzenten George Martin proben und aufnehmen. Zuvor besuchte Görl noch ein letztes Mal München, um seinen Bruder vor den Toren der Stadt zu besuchen. Auf dem Heimweg prallte er mit hoher Geschwindigkeit gegen einen Baum, nachdem er auf vereister Straße die Kontrolle über sein Auto verloren hatte.

Görl verbrachte ein halbes Jahr im Krankenhaus und in einer Reha-Klinik. Die Ärzte bemühten sich mit aller Kraft, sein Leben zu retten. Sein rechter Arm war zertrümmert und musste mit Stahlimplantaten rekonstruiert werden; seine Beine konnte er mehrere Wochen lang nicht bewegen und musste das Gehen neu lernen. Robert Görl konnte sich nur kurz aus der Lebenskrise befreien, dann stürzte er wieder ins Nichts; dieses Mal jedoch eröffnete ihm das Nichts sofort neue Möglichkeiten. Als er aus dem Krankenhaus entlassen wurde, kehrte er in seine Wohnung zurück, die jedoch leer war. Seine Freunde in München hatten nicht mit seinem Überleben gerechnet und seine Habseligkeiten unter sich aufgeteilt; eine Frau erzählte ihm noch Jahre später stolz, dass sie unter seiner alten Bettdecke geschlafen habe. Doch er vermisste nichts davon, weder die Bettdecke noch seine anderen Besitztümer; auch Musik zu machen, hatte er keine Lust. An das Album, an dem er vor dem Unfall gearbeitet hatte, dachte er in dieser Zeit kein einziges Mal. Stattdessen ging er nach Thailand, um Mönch in einem buddhistischen Kloster zu werden. Drei Jahre verbrachte er dort, bis ihm klar wurde, dass er das, was er suchte, nicht in einem Kloster finden konnte, sondern nur in sich selbst. So kehrte er im Sommer 1992 nach Deutschland zurück und tanzte auf der Loveparade in Berlin zu Musik, die klang, als stamme sie direkt von D.A.F. ab. Die nächsten Jahre verbrachte er als Techno-DJ, aber das ist eine ganz andere Geschichte.

Eine Kassette mit den unvollendeten Liedern aus Paris, den dramatischen, eindringlichen, manchmal übel zischenden, aber immer zart gearbeiteten Stücken, die Robert Görl während seiner tiefsten Lebenskrise aufgenommen hatte, tauchte Jahre später in einem Koffer auf, den er in der Scheune seines Bruders deponiert hatte. Es sind musikalische Skizzen, Görl sagt, er habe nie den Wunsch verspürt, daraus ein richtiges Album zu machen. Es sind Skizzen, aber in ihnen spricht eine ganze Zeit zu uns, ein Leben an einem Wendepunkt, und das Licht, das über den dunklen Untergründen der übel riechenden Beats schimmert, weist uns in die Zukunft: Alles endet, wo etwas beginnt.